Nia DaCosta’s slasher flick “Candyman”, a simultaneous reboot of and sequel to the 1992 movie of the same title, arrives on to cinema screens fully formed and awash with meaning and symbolism. Co-written by DaCosta alongside Jordan Peele and Win Rosenfeld, the effort is only DaCosta’s second directorial piece before graduating up to 2022’s “The Marvels” for her third, a now familiar fast-track route through Hollywood which will render her the youngest director of an MCU movie ahead of previous navigator of the same journey, Ryan Coogler. This buzz is notable given the stubborn paucity of high-profile female directors, and much deserved on this evidence.

As immaculate directorially as “Candyman” seems, it nonetheless bears so many of the hallmarks co-writer Jordan Peele has made his own across only two previous films directed in the shape of “Get Out” and “Us”, the former in particular a powerful acclaim magnet, the latter a somewhat underrated gem; most prominently, Peele’s vast subtextual architecture and his brilliance of pop-cultural touch. Like any horror film worth its salt, “Candyman” expertly confects its authenticity from a grab-bag of conceptual sources, made all the more challenging by its having to juggle many of the elements inherited from the narrative of the 1992 original, which was but one year removed from the magnum opus of this feat within the slasher and horror spheres, “The Silence Of The Lambs”. As we shall explore, it aces this feat on its own terms.

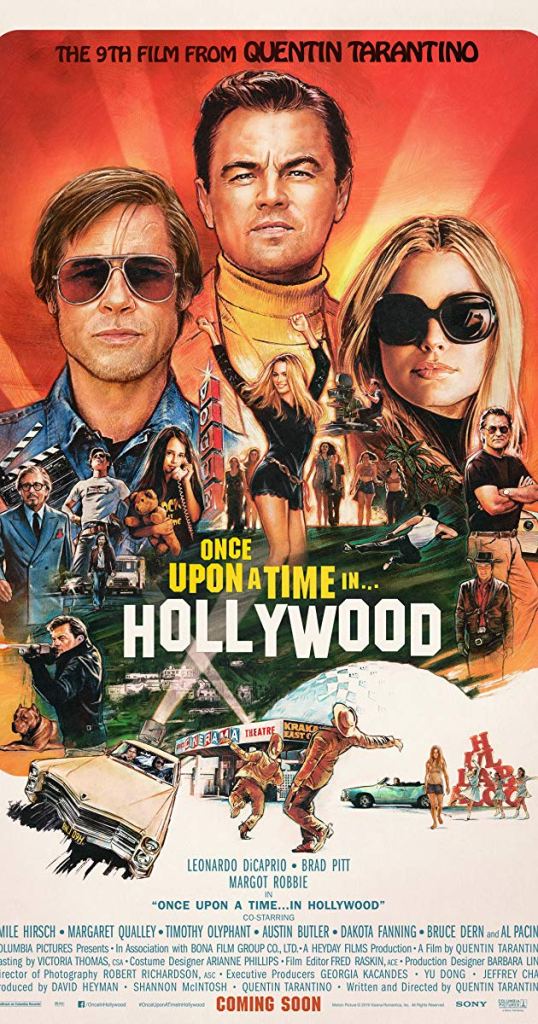

Those devices from the original movie, be they based in storytelling or in theory, were already irresistible, and the new film sagely makes no attempt to step away, instead incorporating and sometimes flipping them to immense effect. The chief promotional posters of the two aforementioned 90s films are informative in this regard; “The Silence Of The Lambs” features a moth covering a mouth, the original “Candyman” goes with a bee crawling over an eye. Both are adapted from novelistic work, but utilise the potency of cinema to amplify the composite parts of their stories and surrounding media.

This is instructive as a general guide to film-makers, and horror-makers especially. DaCosta, Peele and Rosenfeld proceed accordingly. The original setting, Chicago’s infamous Cabrini-Green housing projects, is remixed through the lens of gentrification in the contemporary film, blending in sociopolitical context with ease. While the specific avenue perhaps goes underexplored as the film develops, it acts as an in for Yahya Abdul-Mateen II’s burgeoning but doubtful artist Anthony McCoy, and flows into a generalised soup of racial injustice, sat firmly in the movie’s crosshairs.

At a lean and utterly fruitful 90 minutes, “Candyman” is exquisitely paced and plotted, with nary a wasted frame. Those plot components really are delicious, from the moment the studio imprimaturs appear reversed on screen in foreshadowing reference to the centrality of mirrors in the Candyman story. The chilling, eerie opening credits are superbly scored, with disorientating, upended graphics paying tribute to the Chicago setting and the psychogeography of the story (and, indirectly, positing an alternate version of Wilco’s cover art for “Yankee Hotel Foxtrot”, the Marina City towers). These smile-inducing lower key moments are classic Peele cornerstones, from the man whose “Us” (and its trailer specifically) irreversibly repositioned Luniz’ 1995 smash “I Got 5 On It” as a horrorcore anthem.

Some outlets, understandably drawn into Peele’s contribution to the film, billed “Candyman” as something akin to ‘this year’s “Get Out”’. While race is pivotal to the story, in structural terms this seems very misleading. “Get Out” was a masterpiece in the subversion of audience expectations; anyone who didn’t leave every item of psychological baggage at the screen door was liable to ride the rollercoaster. The film was grandly metaphorical, allowing for a useful degree of stealth in the promotion and plotting of the movie, but focused heavily on what can be broadly described as liberal complicity in racial oppression, certainly in a US-specific context. The ingeniously-titled “Us”, to take a quick detour, was contrasting; while race remained a part of the package, it was class, nowadays mistakenly much-maligned as a theme, and inequality which the film targeted in a decidedly high-concept but quietly intersectional fashion.

The thematic and narrative scaffolding of “Candyman” is much different to either film, and “Get Out” in particular. From the outset, there is an overtness of theme in the plotting which was absent from “Get Out”, where screenwriter intentions were deeply submerged. Abdul-Mateen is excellent as McCoy deteriorates into body horror while his artistic fortunes simultaneously threaten to prosper, as is Teyonah Parris as his girlfriend Brianna, an art gallery director, conveniently enough. Some of the most telling moments can be found between script lines, in the various conversational scenes between the pair, Brianna’s brother and various other associates, which reveal the flick’s worldview on race and art, unsurprisingly a key concern in the film’s scenes. Some of these zingers are as cutting as Candyman’s hook.

The same goes for dialogue between McCoy and the snooty, ridiculous art critic Finley Stephens, whose condescension is potently white, middle class and ultimately opportunistic, but representative of a world into which Anthony and Brianna are, in what seems a materially simplistic but spiritually destructive choice, hoping to advance further. If viewers find themselves pondering why, that is of course intentional; the question of whether black advancement through white structures of society and imagination can ever really represent emancipation is posed.

The film does therefore match “Get Out” in being largely concerned with the imposition of violence on racial minorities. The reflection of this in McCoy’s disintegration through his art, once he is exposed to the Cabrini-Green legend of the title character, is another delectable line of the plot which stands tailor-made for the hands of a director and writer pairing as glowed up as DaCosta and Peele are currently.

Nonetheless, as mentioned, the parallel is far from direct. By interrogating the role art has to play in ending black oppression, if any, “Candyman” toys tantalisingly with black guilt and complicity, potential dynamite for a scriptwriter, but handled sensitively here. The look on Brianna’s face as another gallery director soliloquises that the roots of her enthusiasm for hiring Brianna in fact grow from her partner’s rising stock after his works on the Candyman are connected to the film’s grisly murders is brilliantly shot and perfectly acted in silence, a thousand yard stare which encapsulates the complexity of their own relationship and the film’s thematic fault lines.

Thus, like the mirror images throughout “Candyman” which are imperfect rather than bearing the symmetry we would normally anticipate, the reflection some may see between “Get Out” and this flick is not sublimely drawn. The fact that this inversion of mirroring itself mirrors the content of “Candyman” is highly paradoxical, but we do not need to peer beyond the confines of this film to find another, more relevant example. The film is bookended by scenes of police violence and injustice against black people. Every instance of the story’s notorious centrepoint, that uttering Candyman’s name in the mirror five times will summon him, is coloured by his gruesome dispatching of whoever follows the instructions. The lone exception occurs in the climactic scene, whereby the fabric of this arrangement is completely altered. Structurally speaking therefore, via any of the many scenes in the film featuring a mirror, the work as a whole is littered with metonymy.

The final scene bears a more significant meaning in relation to the direct thematics at hand. The audience cannot be certain that the stated switch in dynamics we have witnessed is permanent, by virtue of the film concluding, although it does so in a manner which seems self-consciously ripe for sequels. We already know via the character of William Burke, the main conduit of information to McCoy and pitched perfectly shiftily by Colman Domingo, that the Candyman legend encompasses multiple iterations of the supposed monster, detailed visually and enticingly via shadow puppetry which seamlessly interweaves critical aspects of the original film. In one of the movie’s most important quotes, Burke states “Candyman ain’t a ‘he’, Candyman’s the whole damn hive”. This is delivered amid myriad explanatory twists as we approach the movie’s denouement, all of which embolden the considerable subtext of the story at a tornado’s pace.

That is to say, Candyman is representative of racial injustice and suffering at large. The ultimate call-back is to the character’s origin story, that of the 19th century artist brutally tortured and murdered for falling in love with a wealthy white woman. It seems incorrect to claim that the 1992 original was ahead of its time in espousing these themes when the Los Angeles riots occurred in the same year, but even for a tale as old as America itself, the lore of the Candyman universe seems to slot appallingly well into the young decade that is the 2020s, with audiences stuttering to catch up to the aesthetic and topical sequencing of the original in the years following its debut.

As ubiquitous an icon as Candyman is therefore rendered come the film’s closure, we can read much into the eventualities which unfold. The film is an interrogation of the reform cycle and its relationship with predeterminism. With the conclusion thoroughly subsuming our protagonists into the endemic savagery McCoy’s art looks to reflect and examine, the film asks whether legal mechanisms of reform are superior to violent ones, whether either achieve progress quickly enough and whether artistic endeavours have any role to play in the pursuit of justice, as well as whether any of these options or the outcomes of such choices are inevitable. The plotting of the film is undoubtedly cyclical, if we isolate the progression and fate of McCoy’s character and the way this relates to the underpinning provided by both the themes and the multi-layered narrative, a most sturdy bedrock.

Another keystone unveiled by the film’s development, in its final stages in particular, is the prevalence of unreliable narrators. “Candyman”, as expected from Peele, packs a certain degree of self-reflexivity, and is undoubtedly aware of the folkloric strands entangled within the various levels of its plotting. The importance of who tells a story and why is underlined very effectively as the story unfurls and blossoms, undoubtedly a pivotal point in a work which leverages the state-sanctioned killing of innocent black people as part of its didactic brew.

McCoy titles his first exhibition after learning of the Candyman yarn “Say His Name”, offering a mirror by way of invitation for the observer to engage with the art in a more immersive way than can be comfortable, with extremely bloody consequences. While we’re talking promotional posters, the new film’s art prominently utilises the similar “Say It”. The interplay between this element of the film series and the killing of Breonna Taylor by police officers in Louisville, Kentucky in 2020, which would (eventually) prove to be a major part of civil unrest around racism in the US and globally last year, seems inextricable. “Say Her Name” became the hashtag and slogan of protests against the slaying, another chilling, off-kilter mirroring linked to the iconography of “Candyman”. Similarly, having ventured down this street of thought, I was unable to ignore the similarity between the names of Breonna and the character of Brianna here.

While some believe that the surge in Hollywood focus on American racism since the early 2010s is sullied by the obvious financial motivation of the studios, it must be contended that films as intelligently and pointedly drawn on the issue as “Candyman”, which in this installment bucks the trend of pointless remakes and toxic franchising, will remain totally essential for as long as racial inequality perseveres. With the wrong people continuing to tell the stories, that will remain a long time.