“Once Upon A Time In Hollywood” is, if virtuosic filmmaker Quentin Tarantino is true to what he once claimed, the auteur’s penultimate movie prior to his eventual curtain call with a tenth and final film in the presumably not very distant future. Tarantino’s films have been among the most acclaimed and academically dissected of the last three decades, and this latest features no shortage of his stylistic calling cards, continuing some of the patterns which observers of his work have seen emerge steadily over the years. Since “Reservoir Dogs” back in 1992, Tarantino’s films have always glowed with the touch of a true cinephile. This flick really takes that aspect of his work to its logical conclusion. The film depicts interweaving storylines during the golden age of Hollywood, specifically the cultural cliff edge that was 1969. The tone and photography are similarly celebratory and effervescent, as is the outstanding soundtrack of contemporaneous tracks which again expertly evidences Tarantino’s sublime traversing of cultural ephemera, while simultaneously exploring a deep sense of loss; of a cultural moment and, in my view, so much more.

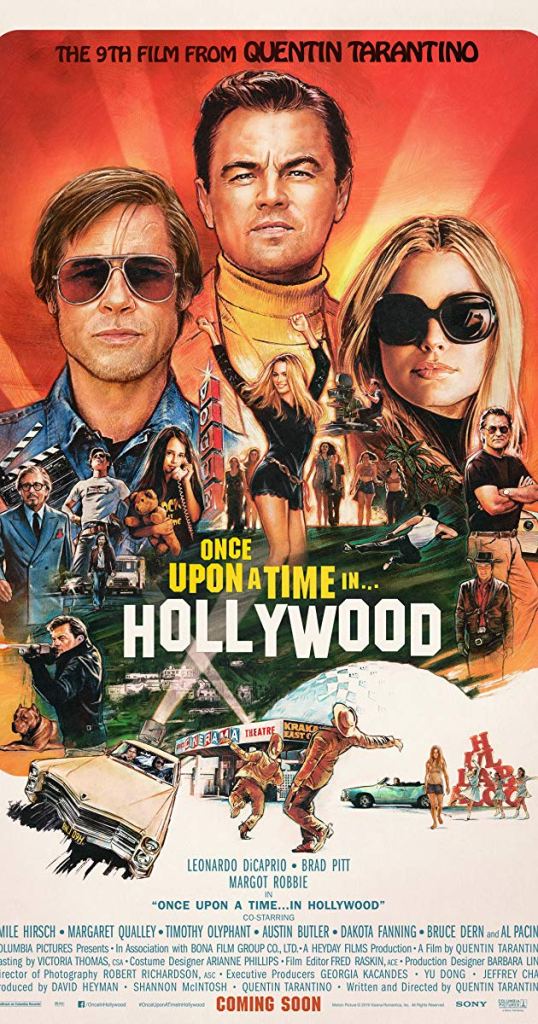

The main focus is on Leonardo DiCaprio’s ageing actor Rick Dalton, becoming all too aware of his own mortality amidst an impending descent into European Spaghetti Westerns, after a sobering encounter with Al Pacino’s casting agent. Brad Pitt is Dalton’s dog-loyal stuntman and glorified driver Cliff Booth. Meanwhile, Margot Robbie is Sharon Tate, living next door to Dalton with her husband Roman Polanski. These are the three most notable roles in what is a lengthy and star-studded cast. Reunited with Tarantino, DiCaprio is clearly having a lot of fun here; equal parts tragic and hilarious with sometimes little more than a flick of the head or facial expression. His scenes with child actor Julia Butters are among the film’s most magical, in what is generally a very slow-burning piece. Pitt, also back with the director, puts in one of his most memorable late-career turns. Although generally seen merely prancing around Hollywood, Robbie is exquisite on screen. None of this excellence seems to be a coincidence in Tarantino’s possession.

The Hollywood setting allows Tarantino to indulge in a Greatest Hits-style scene parade; a schlocky Nazi-killing spoof is a naked nod to the masterful “Inglourious Basterds”, while the generous dollops of Western tribute, which clearly locate the director in his element, continue in the vein of his last two movies; that other outstanding film “Django Unchained” and the underrated chamber piece “The Hateful Eight”. Incorporating fourth-wall breaches into the set up, this is pure playground territory for an individual of Tarantino’s razor-sharp writing prowess. These scenes are those in which the love and tribute for the golden age of Hollywood are most keenly felt, reminiscent of, though not as extensive or varied as, the Coen Brothers’ playfully pitched gem “Hail, Caesar!” In my previous take on Ari Aster’s “Midsommar”, I described as ‘synthetic authenticity’ the ability of writers to make divergent aspects appear natural, even historic, in the context of a story. Tarantino has been a master of this artform, fusing the Western with martial arts and Samurai flicks (“Kill Bill”), and with American race history (“Django Unchained”, which with its incorporation of the apocryphal concept of ‘Mandingo fighting’ and an embryonic version of the Klu Klux Klan, to name but two examples, is an exhibit par excellence of the technique) in ways which have made generations of discerning film fans swoon. There are no finer hands through which to experience a romantic fictionalisation of the era.

All of this said, to truly move on to some of Tarantino’s specific trademarks, we start to encounter some of the most interesting and perhaps troubling aspects of the film. One of the patterns I mentioned earlier has been Tarantino’s swing towards the revisionist in the second half of his career. In “Inglourious Basterds” and “Django Unchained” he dealt in only the grandest of scales and panoramas, tackling Nazi Germany and Antebellum-era American slavery respectively, in what were explosive, exhilarating, maddeningly entertaining reimaginings of history; the deepest of revenge flicks writ large. The former was the film which sucked me into cinema when I first saw it in 2011, and ran around the house from sheer giddiness for a couple of hours afterwards. Although “The Hateful Eight” was not of this vein, it explored racial tension in the hangover of the American Civil War in a most understated fashion, nestled between the lines of its rich, engrossing script. In this film, Tarantino is back to taking a red pen to some of the history which stalks our contemporary imagination most vividly, but his focus is much more precise, zooming in to a specific incident in ’69 Hollywood. For anyone who knows the story of the Tate murders by the Manson Family cult, Tarantino’s film is laced with a venomous foreboding, which tastes all the more potent when coupled with Rick Dalton’s mourning as his career begins to slowly, tantalisingly unfurl. The entire script fizzes as it builds to a denouement which will allow Dalton to eclipse his supposed shortcomings while offering the viewer the comfort of seeing history remoulded into a more comforting, salving alternative to its vicious reality.

So many of Tarantino’s films have been about time, even before he began to take a scythe to the most discomfiting of historical events, as seen from his liberal Los Angeles vantage point. His masterwork, 1994’s “Pulp Fiction”, remains one of the most sparkling and canonical works of cinematic post-modernism, especially to mainstream audiences, as a result of its non-linear narrative structure. Tarantino has employed the method several times, though never as satisfyingly as in that film, where it was one of those high five-inducing, “why-has-nobody-done-it-as-well-before?” strokes of genius. This kept his stories alive with the possibility of subversion, but largely as an illusion generated by structural fragment. The time in these films still moves as one thread, just like time as we experience it in life. The same applies to his more recent revisionist output, including this film, but in these cases while we sometimes experience the same method from Tarantino, the films themselves represent alternative realities with different outcomes to those in our own timeline. The source of the change to the timeline is never conclusive. We see overlapping, layered storylines between Dalton and Booth on one side and Tate and Polanski on the other, until they begin to converge via the Manson Family angle. We see non-linear storytelling in a particularly riotous segment involving Bruce Lee, where Booth reminisces about why he is unlikely to be hired by a particular person. As examinations of what time means, these are more bludgeoning, direct but visceral cinematic levers than the intricately constructed mazes of Christopher Nolan, whose output is also almost all an interrogation of how time is experienced, but instead questions whether it is possible to alter future events by altering the perception of time, rather than changing history.

When we arrive at the moment where it is time to present that altered version of events, there is no denying that Tarantino does so devilishly. He reaches for that most Tarantinian of moves, the aestheticised violence served with lashings of wicked humour. Even by the standards of Tarantino flicks, the brutality somehow manages to be moved up a notch or two, intensified by the film’s gradual climb and the fact that the pivotal action of the movie is all packed into one tinderbox of a scene. I give Tarantino particular credit for avoiding the boring overreliance on guns which is typically omnipresent in not just most of American cinema (including his own catalogue) but cinema in general. That said, in one of the film’s most chortle-worthy frames, Mikey Madison’s Manson cultist is roasted with a flamethrower, but this brings a certain novelty to proceedings! This climax is a furious eruption of violence, which brutally refutes historical accuracy. I have no objections to that as a storytelling device, least of all as a fan of Tarantino’s oeuvre.

It is perfectly possible to say that a piece of cinema is of an excellent quality, as “Once Upon A Time In Hollywood” is, finding an elite filmmaker still somewhere in a never-ending prime, while also acknowledging that it decants some interesting implications. It is clear when studying Tarantino’s work that his films are of what we would today refer to as a ‘liberal’ persuasion on issues such as, most prominently, race, if we are employing a binary dichotomy of socio-political markings, which is obviously dangerous in and of itself, and has perhaps irreversibly corrupted the American public sphere already. Tarantino’s relationship with liberal identity is less comfortable when we consider that this is the first film he has made in his career without the involvement of Harvey Weinstein, after the producer was heavily alleged in 2017 as a grotesque and prolific sex criminal. On a different but still related note, the most interesting moment of the film left dangling in mid-air is an isolated micro-scene which implies that Booth murdered his wife, which goes unexplored for the remainder, in a way which ought to complicate viewer sympathies somewhat. All the same, the events of this film, in line with those of “Inglourious Basterds” and “Django Unchained” before it, are symptomatic of a political problem in a climate where people who are apparent fans of Nazism and the subjugation of black people can freely parade around expressing such views without shame, all the way into the highest of political offices.

The problem I am referring to is that by abandoning the future in favour of attempting to win battles which were already lost in the historical past, liberals (of which I am one) are widely vacating the political space needed to win the arguments of the day and thereby secure electoral success. It seems to be fitting that the film was released exactly 50 years after the particular calendar year it paints, with all the tumult of Woodstock, the Moon Landings and, yes, the Manson murders. This was a year in technicolour, both brilliant and barbaric, giving little inkling of the dreary, insidious 1970s. Tarantino, on behalf of liberal culture at large, mourns the end of a chapter of American history, using a reframing of the Manson murders as a particular incident through which he can summon an anaesthetising, becalming nostalgia, to which Rick Dalton’s redemption in the face of certain defeat is a most blinding of mirrors. Even if you interpret it as sad to see this from a figure of Tarantino’s stature, it remains spectacular and dizzying story-writing in so far as sociocultural significance goes. One of the most surprising omissions of the film is that the white supremacist ideology running through the Manson cult is not referenced, which would have made the themes I mention here more overt and would have made the murders’ centrality to the plot of this movie more obvious given Tarantino’s vibrant recent tradition of discussing race in his works.

As mentioned earlier, there is reason to believe that Tarantino will make his final film the next time he sits in the director’s chair. One of the most interesting and logical of the ideas he has mentioned for a future film, of which there have been many in a largely speculative and scattershot fashion, would be a biopic of the 19th century white abolitionist John Brown, who took up arms against slavery. What we can tell from “Once Upon A Time In Hollywood”, and all of Tarantino’s recent films if not every film he has ever crafted, is that the subject matter would be in more than capable hands. However, since this is the only biopic which he has expressed an interest in making, it would be most intriguing to see if Tarantino could resist the urge to tinker with the past in a way designed to massage the insecurities and doubts of modern day liberals unable to articulate a vision of how a self-confident, equal and peaceful society would look in future and be brought into being today. Brown was, after all, convicted of treason by the Commonwealth of Virginia and hanged. Such narratives continue to cast a shadow over the daily news bulletins of modern America, and as a most prominent filmmaker, for whom this film became the second highest gross of his decorated career behind “Django Unchained”, Tarantino is at the very epicentre of the culture wars. Even if his stories and the forms in which he tells them throw up some discrepancies and shortcomings, cinema will be a far less gripping and gloriously engaging field when he is gone.