Recently, I took a bath for the first time in a long time. Since moving home two and a half years ago, I calculate that I have graced my bathtub a grand total of five times. A casual and entirely unscientific straw poll of associates suggests that people generally lean towards showers, although not exclusively. Yet many agreed that baths are the more enjoyable, when we bother to enjoy them. A cursory glance at the Internet suggests that if managed correctly, showers are the more water and energy efficient option against baths, although this doesn’t seem to be a motivation for most people. I suspect that, much like many other vital, recharging activities such as sitting around doing and thinking about nothing and, erm, sleeping, baths are just another casualty of our contemporary, supercharged, late capitalist lifestyles. This seems inextricably tied to the fact that where bathing was once a very public affair, it is now utterly private, and therefore has little anchor in a world which demands that we let things play out in the public glow of social media. Yet like sleep, the bath is clearly invigorating and allows us to be reborn. It is literally and figuratively cleansing and seems to transform me each time I take the dip. The moments alone with only your thoughts can be reimagined as an act of resistance in this context. So exactly why are baths portrayed as locations of danger in much of our culture? I’d argue that this is evidence of their importance as a phenomenon.

Time and time again in much of our canon, the bath is a perilous spot. It seems that this is because bath-time finds us at our most vulnerable. Detached from a world from which we rarely escape, experiencing utmost relaxation and with nothing at all to hide (unless you don’t take baths naked, in which case OK), this puts us at our furthest removed from our daily demands and tribulations. It is a rare state of peace. My friend Sandra described it thus when I brought up the subject: “I believe people love baths because it feels a bit like how we felt when we were in the womb. Warm and safe…I truly believe it triggers that feeling in our brains. That’s why people get very relaxed; it reminds us of a time where there was nothing to worry about”. This fascinated me and is very much on to something, but raises intrigue since, as I shall discuss, the bath is regularly portrayed not as a haven, but a dangerous zone. There is an interplay here, a convergence between life and death which makes the bath so powerful.

One of the most evocative depictions of bathing in Western culture is a gruesome one. This is “The Death of Marat”, the 1793 painting by Jacques-Louis David, immortalising the murder of his fellow Montagnard and French revolutionary leader Jean-Paul Marat, at the height of the French Revolution, by the Girondin sympathiser Charlotte Corday. The fact that Marat was taking a medicinal bath to treat his notable skin ailments adds a layer of vulnerability, although a layer of complexity is certainly added on top by Marat’s significance during the Reign of Terror and the September Massacres in particular. This painting evidences a different convergence, of the mundane with the electrically political. This is iconic stuff for sure, and an immortal portrayal of the exposure involved in taking a bath. Corday strikes Marat at his weakest.

Contemporary equivalence might be drawn with the shower scene in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 horror classic and seminal slasher movie, “Psycho”. Now, I know this occurs in a shower and not a bath but it delves into so many similar themes and preys on such a rich vein of contemporary anxiety that it seems churlish to force the difference. Barely a canonical American horror film has passed since without conjuring up our most horrible, shared, public fears about the yoke of domesticity and what may lurk on the other side of a (in this case, shower) curtain. By all accounts, “Psycho”, and the shower scene in particular, was considered in equal parts revolutionary and abhorrent depending on who was asked. Cinema-goers had never seen anything like it on a mass scale. The cinematography, the score, the image of trickling blood circling the plughole, are all irresistibly imprinted on our cultural retina. The scene is nauseating, features fluid but undeniable sexual elements and marks the point in Western culture when violence, preferably with added sex, became an essential form of both entertainment and commerce. This is the epicentre of a head-spinning sociocultural vortex. What makes the scene even more significant for me is an often overlooked fact. Earlier in the scene is the first occurrence of a toilet being flushed in American cinema. This shattering of a, in hindsight rather weird, taboo is usually understandably forgotten, but clearly incorporates the bathroom as a whole into the stage on which Hitchcock orchestrates an insurrectionary unchaining of mass repression. Every theme involved is just as relevant to the bath, that other porcelain motif of the ideal home. The theme continues to be recycled for less stellar horror films, such as in 2000 flick “What Lies Beneath” and its accompanying promotional material.

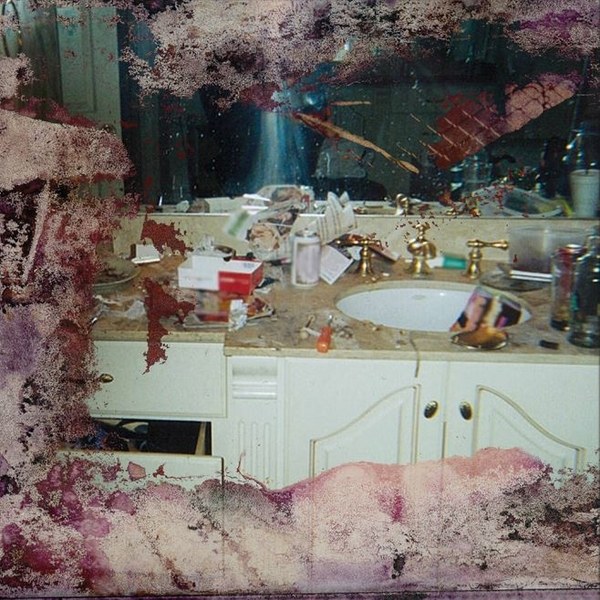

Those are just two of several of our most prominent examples of how the bath intertwines with mortality. Doors frontman Jim Morrison, countercultural prophet and one of the most notable members of the 27 Club, was found dead in a Paris bathtub in 1971. More recently, Whitney Houston was discovered in a similar position, in Beverly Hills in 2012. Kanye West paid a reported $85,000 to adorn the cover of Pusha T’s 2018 “Daytona” album with a picture of Houston’s fatal bathroom, a crass and tasteless act on one hand, but also suggestive of the fact that West understands and channels controversy as well as ever and also appreciates the narrative undercurrents involved in the circumstances. The shot is morbidly fascinating as a twisted photo negative of David’s aforementioned painting and plays with the same horror in a modern context. Musical giants are our modern revolutionaries and like Robespierre, Saint-Just and indeed Marat, they seem to desire a temporal agelessness which currently remains out of their reach. As pleasurable as it can be for each of us, the bathtub is an inglorious enough rock on which to dash the ships of their otherworldly dreams.

Some 400 years earlier was the time of Hungarian countess and alleged serial killer Elizabeth Bathory, who reputedly bathed in the blood of her virginal victims in order to preserve her youth. Although this slice of yore is reportedly in fact a timeless fiction, at least so far as the bloodbath element of the tale goes, it is as evocative a form of cultural myth-making as the deaths of Morrison and Houston. Besides, it is easier to be seduced by such a folkloric yarn when it would make Bathory arguably the best ever example of nominative determinism (run close for me by the American Football cornerback Buster Skrine!). Nothing better summarises how the bath edges us closer to rebirth and death simultaneously than Bathory utilising murder in pursuit of vitality. When we bathe do we yearn to return to the womb as Sandra suggested, or do we surrender ourselves to forces which may undo us in the hope of emerging even better than when we plunged? The thrill of not knowing is part of why we should make the exploration more regularly if we can.

Not all of our touchstones on this topic are as doom-laden or as leaden. In the 2010 comedy “Hot Tub Time Machine”, after travelling back to the 1980s via a time-travelling hot tub (come on, it’s a form of bath!), one of the protagonists witnesses his own conception in the most existential of the examples I am listing here. The gravitational pull of the thematics surrounding water appliances on the psyche of writers is seemingly very strong. When Alan Partridge looks to help listeners to his Norfolk Nights radio show relax in “I’m Alan Partridge” during his laughable ‘Alan’s Deep Bath’ segment (“brought to you by Dettol”), he can’t help but qualify his mindful instructions with the caveat “don’t fall asleep and slip under; some terrible statistics about that”. Although obviously played for laughs, and successfully, Steve Coogan and Armando Iannucci cannot help but spike the idea of an inviting, soothing bathing experience with a shot of danger and impermanence.

How should we read all of this? If we all take more baths, could we change the world? Are cultural markings of the bath (and wider bathroom) as a hazard a form of unconscious, or even conscious, propaganda? Perhaps not quite, but British governments presumably only reach for the hosepipe ban in drought conditions because a bath ban would be practically unenforceable. I take the evidence of the bath as an icon of potential disaster and of the venue of a complex dance between forces of life and death in popular culture and beyond merely as proof of the state of deep and profound reflection it allows us to access. This places us uniquely in a position of exposure as discussed, which is fertile staging ground within cultural frameworks for the navigation of issues of politics, society, the impossibility of immortality and an incessant striving to recover a childlike sense of contentment. When we bathe, we unplug from the matrix, we care for our mental health and we grant ourselves an essential rejuvenation. In doing all of these things we rebel, which is why we should bathe more.